The Cherokee Homeland

Before the arrival of Europeans, the mountain region of what is today Western North Carolina was the center of the Cherokee homeland. Here, Cherokees built their towns and farmed the valleys formed by the Tuckaseegee, Little Tennessee, Hiwasee, and other rivers. This region holds some of the most significant and sacred Cherokee places, including Kituwah, considered the mother town of the Cherokees and a site of great religious, cultural, and historical importance. Today, these mountains are still the home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the descendants of Cherokees who sacrificed tremendously to remain in the Southeast. In Western North Carolina, the Trail of Tears is not only a story of loss and injustice, but a story of resistance, tenacity, and revival.

Removal Decree

In 1835, a small number of unauthorized Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, exchanging the territory of the Cherokee Nation for $5 million and land in Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. The US Senate ratified the treaty the next year, setting the stage for Cherokee Removal. The US Army, along with state militia forces, built forts and roads in the Cherokee Nation to facilitate the collection of over 12,000 Cherokees, 3,000 of whom lived in Western North Carolina. In 1837, soldiers operating out of Fort Armistead in Tennessee pursued Creek (Muskogee) Indians into the mountains of North Carolina, when Creeks tried to escape their own nation’s Removal by seeking refuge in Cherokee territory. A year later, in 1838, US troops and state militia began gathering Cherokees. In Western North Carolina, soldiers marched Cherokees to Fort Butler (present-day Murphy). From there, the deportees walked 28 miles to Fort Armistead at Tellico Plains and then another 52 miles to reach the Fort Cass emigration depot in Tennessee. From Tennessee, these Cherokees left their homeland via the Northern Route of what became known as the Trail of Tears.

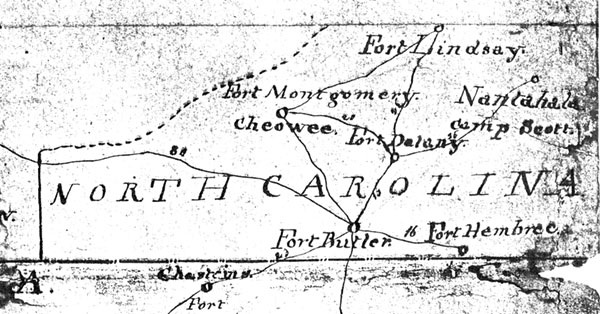

Forts and Roads

Removal was a massive operation, requiring the arrest, collection, imprisonment, and deportation of thousands of people. In order to facilitate this brutal work, the US government surveyed roads, trails, and Cherokee communities.  The Unicoy (or Unicoi) Turnpike, established in 1816, already ran through Western North Carolina, and the road featured multiple waystations to serve livestock drovers moving between Tennessee and Georgia. Fort Butler became the headquarters of the Eastern Division of the Army of the Cherokee Nation. All Cherokee prisoners from North Carolina would pass through Fort Butler, before following the Unicoy Turnpike to Fort Armistead in Tennessee. The Army constructed other posts in the surrounding area: Fort Hembree in present-day Hayesville; Delaney in Andrews; Montgomery in Robbinsville; and the northern-most military installation in the Removal operation, Fort Lindsay, at Almond. What is now the Old Army Road, stretching between Robbinsville and Andrews, was improved over a period of 10 days from a Cherokee trail to accommodate wagons. A segment of North Carolina’s Great State Road stretched from Franklin to Fort Butler and became a major conduit for delivering deportees. The North Carolina legislature approved its construction in 1837 to facilitate the sale and settlement of Cherokee lands after the Treaty of New Echota. The Army also established Camp Scott at the Cherokee town of Aquone, a stop on the way to Fort Delaney from outlying areas. From these collection points, all of the North Carolina Cherokees captured by the army were funneled through Fort Butler to begin the journey west.

The Unicoy (or Unicoi) Turnpike, established in 1816, already ran through Western North Carolina, and the road featured multiple waystations to serve livestock drovers moving between Tennessee and Georgia. Fort Butler became the headquarters of the Eastern Division of the Army of the Cherokee Nation. All Cherokee prisoners from North Carolina would pass through Fort Butler, before following the Unicoy Turnpike to Fort Armistead in Tennessee. The Army constructed other posts in the surrounding area: Fort Hembree in present-day Hayesville; Delaney in Andrews; Montgomery in Robbinsville; and the northern-most military installation in the Removal operation, Fort Lindsay, at Almond. What is now the Old Army Road, stretching between Robbinsville and Andrews, was improved over a period of 10 days from a Cherokee trail to accommodate wagons. A segment of North Carolina’s Great State Road stretched from Franklin to Fort Butler and became a major conduit for delivering deportees. The North Carolina legislature approved its construction in 1837 to facilitate the sale and settlement of Cherokee lands after the Treaty of New Echota. The Army also established Camp Scott at the Cherokee town of Aquone, a stop on the way to Fort Delaney from outlying areas. From these collection points, all of the North Carolina Cherokees captured by the army were funneled through Fort Butler to begin the journey west.

From Doorstep to Deportation

Federal officials and army commanders viewed Western North Carolina as a hotbed of Cherokee resistance, and some feared that an armed Cherokee uprising would break out in the mountains. Cherokees, however, did not resist with violence. Instead, they simply ignored the mandate to remove, planting their crops and building homes until the troops arrived. As one official noted, “There are about six thousand in our neighborhood—their houses are quite thick about us, and they all remain quietly at work on their little farms, as though no evil was intended them. They sell us very cheap anything they have to spare, and look upon the regular troops as their friends. . . These are innocent and simple people into whose homes we are to obtrude ourselves, and take off by force. They have no idea of fighting, but submit quietly to be tied and lead [sic] away.” When the troops began their operations in Western North Carolina in early June, “some of the Indians were already coming in, and being informed that many of them were collecting at a place of worship of theirs, seven companies of us marched thither. . . By night fall about a hundred had assembled. On the 13th some of the troops returned and by the morning of the 14th we were all in with nearly a thousand Indians.”

The first North Carolina Cherokees left Fort Butler on June 18, 1838, but did not leave Fort Cass until late summer or early fall, due to a drought that halted the emigration process by the water route. That delay forced them to languish in the deportation camps for much of the summer, before traveling overland to Indian Territory. Most North Carolina Cherokees were assigned to one of three detachments, numbering around 1,000 people each. Conductors included Jesse Bushyhead, a Cherokee Baptist preacher; Situagi, the headman of Hiwassee Town and Aquohee District judge; and Chuwaluka, or Old Bark of Taquohee. Situagi’s assistant conductor was Reverend Evan B. Jones from the Peachtree Baptist Mission in Valley Town. Chuwaluka’s assistant conductor was J.D. Wafford, also known as Worn-Out-Blanket. Along the Trail of Tears, these three detachments lost 15 percent of their members to disease and exposure. They did not arrive in Indian Territory until February and March of 1839. Most settled in what became the Delaware District of the Cherokee Nation.

Resistance in the Mountains

Though most North Carolina Cherokees submitted to forced removal, several hundred, especially those from the Aquohee and Tahquohee Districts, continued to resist, hiding in remote sections of the mountains and working to avoid the pursuing soldiers. The mountain terrain made locating these refugees very difficult. “After three weeks of the most arduous and fatiguing duty, traveling the country in every direction, searching the mountains on foot in every point where Indians could be heard of we [have] not been able to get sight of a single one,” one officer reported. “Their constant vigilance, perfect knowledge of the country, and the rapidity with which that enabled them to communicate intelligence from one camp to another, has rendered all attempts to capture them utterly in vain.” Some Cherokee families received waivers to remain behind. These included the prominent John Welch, a wealthy farmer and slave owner who cultivated valuable bottom lands near the Valley River. Welch and others encouraged Cherokees “to leave home & take to the mountains,” and they covertly fed and encouraged the fugitives. Declared an instigator of rebellion, the Army seized Welch and held him without charge at Fort Cass. The military only released Welch after Removal was completed. Welch’s farm became a haven for about 100 landless Cherokees who escaped the Army’s net. Dickageeska, one of these homeless Cherokees, recalled that resisting removal came at a steep price, as they were “compelled to subsist on the sap of trees and roots, and nearly all the children belonging to his people died, only two children remained out of a population of near 100 persons.” The Army conducted intermittent attempts to collect the fugitives and remove them as late as October 1838. Nevertheless, by 1840 these Cherokees were “forming settlements, building townhouses, and show every disposition to keep up their former manners and customs of councils, dances, ballplays, and other practices,” as one observer reported.

A Persistent People

Cherokees living at Quallatown, on the Oconaluftee River, were exempt from Removal, thanks to provisions in earlier treaties between the Cherokees and the United States. Known as the Luftee or Citizen Indians, this group eventually coalesced with those Cherokees who managed to avoid capture during Removal to form the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. North Carolina acknowledged the Cherokees’ right to remain in the state in 1868, and the United States eventually recognized the Eastern Band as a distinct tribe. By 1875, political unification of Cherokee communities led to the emergence of six townships. Today, the western-most communities of Cheoah (now Snowbird), Valley River (now Tomotla), and Hanging Dog (now Hanging Dog and Grape Creek) constitute one of these six townships, while the remaining townships are located on the Qualla Boundary, the large landholding established in the vicinity of Quallatown. The Cherokee legacy remains one of survival, persistence, and resurgence, as they have successfully rebuilt their lives in both the West and in the Southeast.